If you have expectations as to whom you might see getting ready to sail off the dock at Manhattan’s Dyckman Marina, you might want to take a step back and reset your expectations. You might want to take a step back anyway, just so you don’t get your toes run over by the crew rolling down the pier. On any given weekend, from May through October, sailors using wheelchairs are making their way to customized boats, looking forward to another day on the water.

Hudson River Community Sailing (HRCS) has been making the waterfront accessible to New Yorkers for 15 years. The organization was founded with a dual mission: to provide leadership and STEM education to NYCpublic-school students, and providing sailing education to the greater community. Opening the organization to adult members and public lessons helped fund staffing and maintenance, but also exposed gaps in who had access to the waterfront.

For more than 10 years HRCS has worked on veteran outreach, beginning with Heroes on the Hudson, an annual all-day adaptive sports event organized by The Wounded Warrior Project and the NY branch of the Veterans Administration,at which veterans can practice kayaking, fencing, yoga, and sailing. HRCS organized the sailing activities, and that led to developing a more extensive veteran’s sailing program with the help of a VA grant.

“The program was not able to serve people with physical disabilities to the extent that we wanted to,” says Robert Burke, HRCS Executive Director. HRCS’s boats were all moored in a fairly choppy part of the midtown, and transferring from dock to tender to sailboat could be difficult for crew with reduced mobility. In 2017, however, things began to change.

Community Programs Director Don Rotzien took the US Sailing Adaptive Course with US Sailing Adult Programs Director Betsy Alison. The course is crafted to consider variables such as equipment, location, the boats available, and (especially) the people who will be using them. Each class is a little different depending on the specific needs of the participants. For example, Alison explains that “teaching to students with autism has come up a lot lately, and that requires more focus on teaching technique than on specialized equipment.” That idea was echoed by Rotzien who remembers that “the basic philosophy of the course is understanding needs through good communication with your new crew member.” After all, he reminds us, we’re not all the same height, weight, or strength. “To some extent, all sailing training is adaptive.”

Of course, it’s not all about technique. Frequently, part of the 3-day course focuses on how to lightly modify a club’s fleet to meet the needs of sailors with a range of mobility needs. One learns to use fenders, PFDs, and lines to engineer a solution on the spot. Rotzien shared a key takeaway: “Don’t be overwhelmed by ‘no we can’t.’”

Executive Director Burke shared how 2017 was the beginning of a big transition. HRCS had been working to expand to a second location at Inwood Marina in northern Manhattan, far from the ferry traffic of midtown, in part to acquire docks and a physical layout to support access to boats to expand whom they could serve. At the same time, HRCS was developing a plan to expand beyond its fleet of aging and cramped J/24’s and had chosen J/80’s, whose open cockpit design was better suited to certain simple modifications than the older J/24’s.

Expansion plans involved an adaptive steering committee, which included an army veteran and avid sailor; an administrator of adaptive sports at the VA; two experienced managers from advocacy organizations; and an adaptive sailor who was an old friend of Burke’s. That friend is Quemel Arroyo, also known as Q, now the Chief Accessibility Office for NY’s Metropolitan Transit Authority. Arroyo first learned to sail as a teenager, before an injury reduced his mobility. One of his teachers was Burke, then an instructor at Outward Bound.

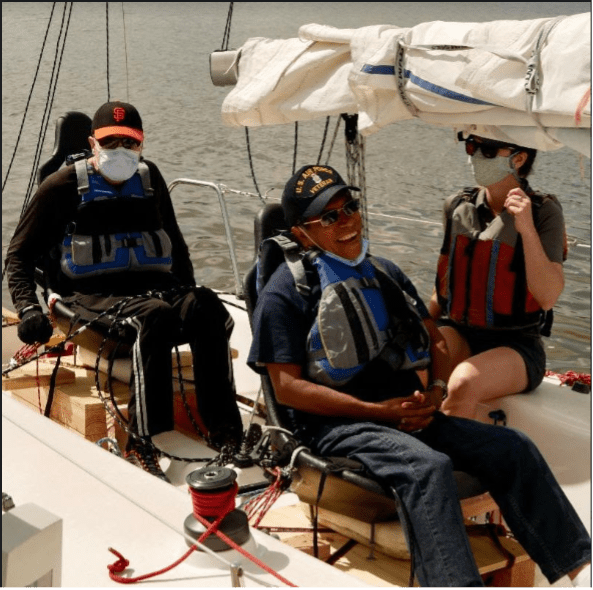

J/80’s began arriving in 2019, and Rotzien got to exercise his adaptive training, remembering that collaboration was key. “Q was a great participant,” said Rotzien. “We spent some time prototyping and improving, and our friends at the VA had been down this road before and suggested go kart seats.” Don developed a chair and helm controls that adapted the J/80 to accommodate participants with spinal cord injuries, including Arroyo. In the fall of 2020, he helmed a J/80 at HRCS’s fall fundraising regatta, Sailing for Scholars.

The pandemic delayed program development slightly, but in the Spring of 2021 the program took its next leap forward. Betsy Alison taught the 3-day course in developing an adaptive sailing program on the Inwood docks. Rachel Szymanski, an HRCS member as well as an Occupational Therapist at the Spinal Cord Injury and Disorder Department at the James J. Peters VA Medical Center remarked, “Everyone involved in the process was very supportive and open to learning about transfer techniques, adaptive equipment, and positioning needs for veterans with spinal cord injuries. There was a great deal of information and idea sharing back and forth, including direct feedback from some of our veteran participants who are avid sailors.”

By the fall of 2021, the organization was looking to hire an Adaptive Program Manager, and Diana Christopher was an ideal fit for the role. As she explains it, “as an occupational therapist, my role is to facilitate an individual’s participation in the activities they want and need to do given a visible or invisible disability.” And with a 100-ton Coast Guard license with an auxiliary sail certification and professional experience as the captain of tall ships sailing around NY harbor, the Hudson is no stranger to her. “I jumped at the opportunity to be involved because it seemed like such a perfect mashup of my skill set.”

The next step for HRCS is to integrate accessible features into all programming. With many of the instructors now familiar with transfer techniques, seating and steering modifications, and related client needs, the goal is to make taking a lesson or going for a sail as a member nearly seamless. It just means letting staff know in advance that you’ll need one of the modifications, which can be set up before the crew member or trainee arrives. HRCS is always focused on safety, and it’s well understood that if things go wrong, they can go much worse more quickly for crew members with a physical issue. As with any new program, and in recognition of the challenges posed, “there will be more training and an even larger emphasis on safety for this particular program” Captain Christopher shares.

So when does HRCS hope to have this in place? “2024 will be the pilot year for an adaptive membership program!”

Sure, but what does it all look like up close?

Nowhere is this more obvious than when a sailor with a disability gets onto a boat. Some will walk down to the boat, but they need a solid shoulder to lean on as they step aboard. Others will roll to the boat on an electric chair. Some will be able to transfer onto the boat themselves. Others may need a varnished plywood board to act as a slide, a stepstool to facilitate moving from one level to another, or something more elaborate, like a hoyer lift you may have seen at a swimming pool. This may be new for you, but for the sailor using a wheelchair, this is part of their daily routine.

The big surprise for many taking the course is that not all modifications are expensive.

For example, the chairs fitted to the J/80 pictured above are go-cart seats that cost $50 each. They are mounted on top of a fender and bolted to a piece of plywood sitting on 4 x 4 runners. The chair is adjustable to account for the heel. You can see red and white lines rove through blocks with a cam cleat repurposed from main sheet hardware. The wooden base is held in place with ratchet straps attached to eyes that are already built into the sole for backstay blocks. When a rear seat is also used (as above) the tiller is replaced with a short piece of lumber, and a line is attached to the new stub tiller with a clove or cow hitch, run through the spin blocks at the pushpit, then forward to blocks at the rear stanchion. Either seated sailor can steer the boat using this line. Swapping between configurations takes about an hour, so a boat is always ready, regardless of the crew.